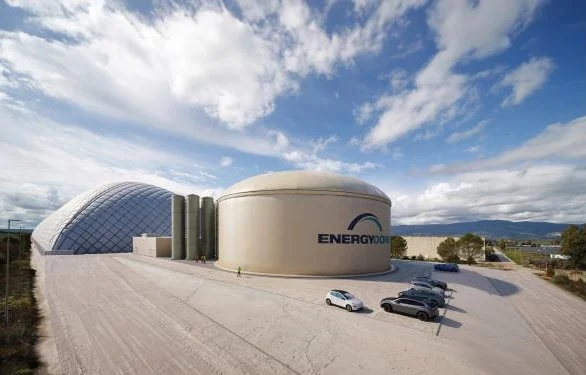

Google has partnered with Energy Dome to deploy long-duration “CO₂ batteries” that store electricity by compressing and re-expanding carbon dioxide. The technology promises long discharge times and low dependence on scarce minerals, useful for powering data centers 24/7. But compared with containerized lithium-ion storage, CO₂ battery plants can need much more land and industrial infrastructure, raising social and ecological questions for global communities and regulators especially in Southeast Asia.

What is the CO₂ battery?

A CO₂ battery stores electricity by compressing carbon dioxide (CO₂) into a dense liquid under pressure and storing it in tanks. When electricity is needed later, the system heats the liquid CO₂, it expands back into gas, and that expanding gas turns a turbine to make power again. The CO₂ stays inside the plant in a closed loop, it is not burned or emitted during operation. This design targets long-duration energy storage (roughly 8–24 hours), bridging the gap between intermittent renewables and continuous power demand.

Energy Dome (the company behind the CO₂ battery) emphasises these selling points: low reliance on rare minerals, long lifetime (30+ years), modular design using industrial components, and round-trip efficiency they report around 75%+. Google has announced a commercial partnership and investment to scale the technology as part of its effort to achieve 24/7 carbon-free energy for its data centers.

The Real Business Logic Behind Google’s CO₂ Battery Projects

Large digital companies run data centers that must operate continuously. Solar and wind produce clean power but not always when demand is highest. That is why long-duration storage (LDS) is strategically valuable. First, it lets companies match renewable generation with 24/7 demand, improving carbon accounting and resilience. Second, For corporate buyers, the CO₂ battery can act as a form of firm energy, effectively replacing expensive fossil peaker plants for several hours. Energy Dome claims dispatch durations of 8–24 hours per installation. ompared with lithium-ion systems, CO₂ batteries avoid major critical minerals (lithium, cobalt, nickel), reducing exposure to mining-related supply risks and price swings.

From the investor perspective, Google’s deal is a credibility signal: a major corporate buyer and strategic partner helps de-risk early commercial scale-up, which can accelerate deployment across markets.

The Ecological Trade-Offs: Lower Mining, but a Larger Footprint

At first glance the CO₂ battery looks greener: no mining of lithium or cobalt for its core working fluid, and a long service life. But environmental impact must be judged across several dimensions, not just which raw materials are used.

1) Land and Industrial Footprint

Independent documents and company filings indicate that a single 20 MW / 200 MWh CO₂ battery plant can occupy around 10–12 acres (4–5 hectares). That is materially larger than many containerized lithium-ion battery sites of similar power capacity, which can be sited more compactly. The larger physical footprint matters in land-constrained regions.

2) Materials and Embodied Carbon

CO₂ battery plants still require steel, concrete, compressors, turbines, and thermal storage. These construction materials carry embodied carbon and local environmental costs (quarries, cement emissions, transport). In contrast, lithium systems concentrate environmental impact in battery cell manufacturing (mining and refineries), with different geographical and social effects. Lifecycle assessments for battery technologies show wide variation, but manufacturing emissions for lithium-ion cells remain a key concern in many studies.

3) Efficiency and Operational Emissions

CO₂ batteries report round-trip efficiency ~75%+, lower than some lithium-ion systems (~85%) but still useful for long-duration storage where duration matters more than peak efficiency. Because the CO₂ circuit is closed, operation itself emits no CO₂, but embodied emissions from construction and heat sources used to re-heat CO₂ matter in lifecycle calculations.

Bottom line: CO₂ batteries reduce one set of ecological problems (mining) but can create others (larger land use, construction emissions). Which set matters most depends on local priorities, land scarcity, community impact, recycling capacity, and grid needs.

The Social Ecology Issue for Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia (SEA) has a blend of dense urban areas, agricultural land, sensitive coastal ecosystems (mangroves), and growing industrial zones. That mix changes how new, large energy plants interact with people and nature.

A. Land competition and livelihoods

Ten acres can displace smallholder agriculture, aquaculture ponds, or community land in SEA contexts where land rights are often contested or unclear. If a CO₂ battery is sited near a city to support a data center, that urban land demand competes with housing and small industry. If sited rurally, it can affect farming livelihoods and local land use patterns.

B. Environmental justice and consultation

Major infrastructure projects in the region sometimes proceed with weak community consultation or uneven environmental review. Large industrial footprints risk being perceived as benefiting remote corporate data centers while imposing localized environmental or social costs on host communities. This raises classic environmental-justice questions: who gains the clean power, and who bears the local impacts?

C. Regulatory readiness and safety

CO₂ battery plants involve high-pressure gas containment. While the systems are engineered for safety, local regulators must be capable of reviewing industrial safety, emergency planning, and land-use setbacks. Some commentary notes that a rupture, while unlikely, would release CO₂ mass quickly and would need plans to avoid harm. In any case, regulators in many SEA countries will need to adapt permitting processes to assess LDS technologies beyond traditional battery rules.

Where CO₂ Battery Projects Can Go Wrong

- Site selection bias - Companies may prefer cheaper rural land far from affected communities, shifting burdens to less powerful stakeholders. SEA governments should set clear siting rules and community benefit requirements.

- Hidden carbon - A focus only on operational emissions can hide embodied emissions in construction materials. Procurement policies and lifecycle accounting should include embodied carbon metrics to compare options fairly.

- Community trust and transparency - Firms must show transparent safety plans, noise and water assessments, and clear community compensation if land use changes. Without trust, projects face delays, legal challenges, or reputational damage.

What Corporate Energy Leaders Need to Weigh Before Choosing Storage

For corporate energy planners, data center operators, and investors in Southeast Asia, choosing the right energy storage technology should start with a clear understanding of local constraints. Land availability and cost are critical factors: in areas where land is relatively abundant and affordable, a CO₂ battery system may be economically attractive and less exposed to mineral supply risks, while in dense urban or industrial zones, compact lithium-ion storage may be more practical. Beyond physical constraints, companies should require full lifecycle accounting when evaluating storage options, comparing embodied carbon emissions as well as capital and operating costs over the system’s lifetime based on local grid conditions and usage profiles. Equally important is the social dimension. Community consultation and benefit-sharing mechanisms should be built directly into procurement contracts and permitting processes to reduce social risk and secure a long-term social licence to operate.

Finally, businesses should consider flexible, hybrid storage strategies, combining short-duration lithium-ion batteries for fast response with CO₂-based systems for multi-hour energy firming, allowing them to optimise land use, system reliability, and overall operational performance.

Google’s commercial agreement and investment help scale the CO₂ battery fast. That increases the chance the technology becomes an option in SEA energy planning and corporate procurement. But scale also intensifies the social ecology question: if many plants are built quickly without careful siting and community engagement, cumulative land and social impacts could be significant. In short, the technology can help the energy transition, but only if deployment is responsible and locally aware.

CO₂ batteries are a promising technology for long-duration storage and corporate decarbonisation. For Southeast Asia, they offer a way for large energy consumers (like data centers) to secure cleaner, firm power without depending on mined battery metals. Yet the ecological gains on one axis (lower mining) must be weighed against land use, embodied construction emissions, and social impacts on communities.

Policymakers, investors, and corporate buyers in SEA should not treat energy storage choice as purely technical or financial. Treat it as infrastructure that sits in space and society, and plan for responsible siting, robust lifecycle analysis, and meaningful community engagement from day one.

References:

- Energy Dome - “CO2 Battery” product page

- Google Blog - “Our first step into long-duration energy storage with Energy Dome.”

- IEEE Spectrum - “CO2 Batteries That Store Grid Energy Take Off Globally.”

- California Energy Commission filing / Energy Dome response (note on land footprint: 10–12 acres per 20 MW / 200 MWh).

- Futurism - reporting on CO₂ battery footprint concerns. (Background reporting on land footprint and safety questions.)

- Nature Communications - i

- MIT Climate / Ask MIT - “How much CO2 is emitted by manufacturing batteries?” (overview of battery manufacture emissions)

Saturday, 10-01-26

Saturday, 10-01-26